With my departure to Berlin less than four months away, I have decided to begin a weekly series on Seated Ovation titled Berlin Diaries. As I continue my research and cultural immersion in preparation for my year in Germany, I will excerpt passages from various books, and possibly interject some of my own stuff as well.

One of the more fascinating discoveries I made at the Northwestern library booksale last year (this year, my greatest finds were a copy of the Denson revision of The Sacred Harp and a vocal score for The Flying Dutchman) was Berlin in Lights, the diaries of Count Harry Kessler from 1918 to 1937. Not only was Kessler a fascinating man, straddling both arts and politics, but he lived in just about the best time to be writing a diary in Germany. It begins with abdication of Kaiser Wilhelm II and Berlin's political crossfire (literally, with shootouts in the streets), continues through the rise and fall of the Weimar Republic, and ends with Kessler cavorting around Paris in exile.

The next month or so of our Wednesday series will probably be devoted to excerpts from the diaries. Here's the first.

------

Wednesday, 5 February 1919 (Berlin)

The Government forces have taken Bremen. The Spartacists have been defeated.

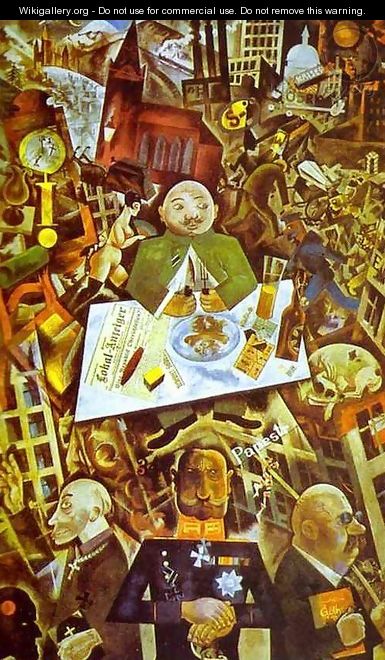

In the morning I visited George Grosz in his studio in Wilmersdorf. He showed me a huge political painting, Germany, A Winter's Tale, in which he derides the former ruling classes as the pillars of the gormandizing, slothful middle class. he wants to become the German Hogarth, deliberately realistic and didactic; to preach, improve and reform. Art for art's sake does not interest him at all. He conceived this picture as one to be hung in schools. I made the reservation that, in accordance with the principle of conservation of forces, it is uneconomic to use art for purposes which may be achieved just as well, if not better, without artistic propaganda. For instance, warnings against venereal disease; here an anatomical exhibition is more to the point. On the other hand there are complex events of an ethical character which perhaps art alone is capable of conveying. In so far as this is the case, a didactic use of art is justified.

Grosz argued that art as such is unnatural, a disease, and the artist a man possessed. Mankind can do without art.

He is really a Bolshevist in the guise of a painter. He loathes painting and the pointlessness of painting as practiced so far, yet by means of it wants to achieve something new or, mroe accurately, something that it used to achieve (through Hogarth or religious art), but which got lost in the nineteenth century. He is reactionary and revolutionary in one, a symbol of the times. Intellectually his thought processes are in part rudimentary and easily demolished.

Deep Cleaning by the Deep State

7 hours ago

No comments:

Post a Comment